Why we must save water

Water covers about 70 percent of Earth’s surface. Yet freshwater—the water we drink, cook with, bathe in, and use to grow food—makes up less than 3 percent of all the water on the planet. Of that small share, roughly two-thirds is locked away in glaciers and snowcaps, while most of the remaining freshwater lies underground as groundwater. This leaves only about 0.3 percent of Earth’s freshwater in lakes, rivers, wetlands, and swamps—the sources most directly available for human use.

These surface waters depend heavily on glaciers and snowcaps, which act as vast natural reservoirs. Over tens of thousands of years, compacted snow has stored freshwater in ice. During warmer months, glaciers slowly release meltwater that feeds rivers and sustains ecosystems, communities, and agriculture, especially during dry seasons. In many parts of the world, this steady supply of meltwater is essential for human survival.

Since around 1950, however, glaciers and snowcaps have been retreating at an accelerating pace. Scientists refer to this period as the “Great Acceleration,” marked by rapid population growth, rising energy use, and expanding consumption. These trends have increased pollution, intensified climate change, and accelerated biodiversity loss. As a result, the rate of glacier melt has risen sharply. Ice loss has increased each decade since the 1970s, reaching record levels in recent years. In the European Alps, for example, glaciers lost about half their volume between 1931 and 2016, followed by an additional 12 percent loss between 2016 and 2021 alone. Overall, scientists estimate that roughly half of the world’s glacier mass has disappeared since the Industrial Revolution.

The outlook for groundwater—the remaining 30 percent of global freshwater reserves—is equally concerning. Groundwater is being depleted at an increasing rate due to unsustainable pumping for agriculture and growing populations; a problem made worse by longer and more severe droughts linked to climate change. Falling water tables, dry wells, and land subsidence are already affecting many regions. If these trends continue, the consequences for human well-being will be severe.

Groundwater is especially important because about half of the world’s population depends on it for drinking water, and roughly 2.5 billion people rely on it exclusively for their daily needs, particularly in rural areas. Globally, groundwater provides about 40 percent of irrigation water and roughly 25 percent of water used by industry.

At the same time, groundwater is increasingly polluted by human activities. Fertilizers, pesticides, industrial and mining waste, and petroleum products have contaminated aquifers worldwide. A World Bank study warns that the widespread use of petroleum since the early twentieth century means shallow groundwater in every populated region of the world should be considered at risk. In the United States, where about one-third of drinking water comes from groundwater, the U.S. Geological Survey estimates that 22 percent of groundwater is contaminated by human-generated pollutants.

Surface water is also under severe stress. A 2024 United Nations study found that more than 40 percent of lakes and rivers worldwide—and over half of major rivers—are seriously degraded or depleted. In Europe, up to 60 percent of waterways are contaminated. In the United States, more than half of rivers and streams and about 55 percent of lakes are considered unfit for recreation, aquatic life, or drinking.

Given the limited supply of freshwater and the growing pressures of warming temperatures and pollution, careful water management has become increasingly urgent. People are often encouraged to conserve water in their daily lives by turning off the tap while brushing their teeth, installing low-flow showerheads, using efficient irrigation systems, and purchasing water-efficient appliances. While these actions are helpful, they address only part of the problem.

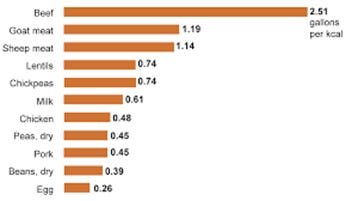

Globally, about 70 percent of freshwater is used for agriculture, mainly to irrigate crops and raise livestock. Producing one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of beef requires more than 15,000 liters (about 40,000 gallons) of water. Worldwide, roughly 36 percent of crop calories are used to feed animals; in the United States, that figure exceeds 67 percent. As the global population grows, this demand will increase, placing even greater strain on water resources, especially in developing countries, where agriculture can account for up to 90 percent of water use.

Feeding crops to animals is also highly inefficient. Only about 12 percent of the calories fed to livestock are ultimately returned to humans as meat or dairy, with the rest lost through metabolism. In contrast, producing fruits, vegetables, and nuts requires far less water to deliver the same number of calories. This highlights the strong connection between dietary choices and water sustainability.

Los Angeles Times

Addressing water scarcity, therefore, requires more than individual conservation habits. It also demands a serious rethinking of the Western diet. Diets in high-income countries are heavily dominated by meat, dairy, and highly processed foods, all of which are especially water intensive. Reducing consumption of beef and other resource-heavy animal products—while increasing reliance on fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains—can dramatically lower water demand without compromising nutrition.

Even modest dietary shifts, adopted widely, could reduce pressure on rivers, lakes, and aquifers, free up water for ecosystems and communities, and make food systems more resilient in a warming and increasingly water-stressed world. Adjusting what we eat is therefore not just a matter of personal health or preference, but a critical part of sustainable water management.