The True Cost of Solar and Wind Energy

One often-cited advantage of solar and wind energy is their relatively low upfront construction cost, especially when compared to building a nuclear power plant. However, common cost estimates for solar and wind installations overlook an important factor: the human cost of extracting the minerals needed to manufacture solar panels, wind turbines, and the batteries required to manage their intermittent energy output.

Solar and wind technologies rely heavily on so-called “critical minerals.” This discussion focuses on three of them: lithium, cobalt, and mica.

Lithium-ion batteries rely on lithium ions moving between the positive and negative electrodes. This movement allows the battery to release electrical energy and be recharged. Cobalt is another essential ingredient, helping stabilize these batteries, prevent overheating, and extend their lifespan. Mica is used in the form of sheets or rigid panels placed between battery cells and modules to act as a fire-retardant barrier, slowing the spread of fire if a battery cell fails.

The mining of these minerals, however, is often linked to serious human rights abuses, particularly in some of the poorest regions of the Global South.

Land appropriation. Indigenous communities in southwestern United States and in South America have seen sacred sites and cultural practices disregarded to make way for lithium mining projects. In many cases, companies fail to obtain Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) from Indigenous peoples before beginning operations on ancestral lands, undermining their rights to self-determination.

Water contamination and depletion. Lithium extraction from underground brines is extremely water intensive. It consumes vast quantities of water in already arid regions, including the southwestern United States and the “Lithium Triangle” spanning southern Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia. This process has depleted local water sources, damaged ecosystems and depriving nearby communities of water needed for drinking, sanitation, and agriculture.

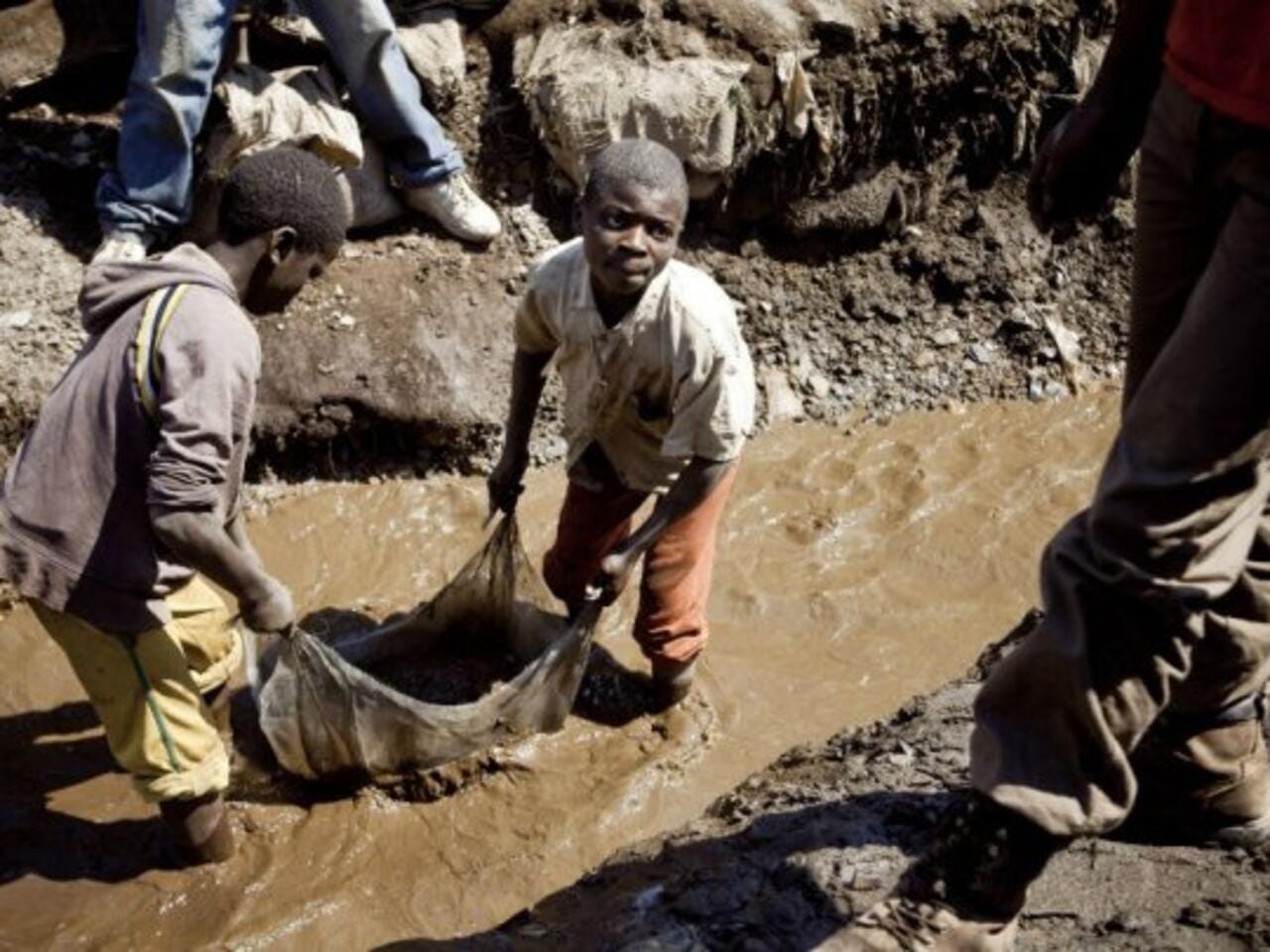

Child labor in cobalt mining. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) holds nearly half of the world’s known cobalt reserves, valued at more than $133 billion. Despite this wealth, over 73 percent of the population lives below the international poverty line of $2.15/day, forcing many families to depend on child labor to survive.

An estimated 40,000 children work in cobalt mines in the DRC, some as young as seven. The International Labour Organization classifies this work as one of the “Worst Forms of Child Labor” due to its extreme danger.

Children often work without protective equipment in unstable, hand-dug tunnels that can collapse at any time. They are exposed to toxic cobalt dust and heavy metals, which can cause respiratory disease and neurological damage. For less than $2 per day, children dig for ore, carry heavy rock sacks, and wash cobalt in contaminated water.

Reports also describe coercive labor practices, including the inability to refuse hazardous work, excessive overtime, withheld wages, and threats of dismissal for speaking out. Some miners report physical violence, including beatings by supervisors or older workers.

Child labor in mica mining. Similar abuses occur in mica mining, particularly in Madagascar, where up to 92 percent of the population lives on less than $2 per day. An estimated 10,000 children work in mica mines, many as young as five. Like cobalt mining, mica extraction is highly dangerous. Children labor in narrow, unstable shafts and inhale mica dust, which can cause serious respiratory illnesses such as pneumonia and silicosis. Protective equipment, clean water, and sanitation are often nonexistent.

Artisanal miners in Madagascar, including children, earn as little as 40 cents per day. For many families, monthly income from mica averages just $6.56. Yet by the time mica moves through the global supply chain and is processed into finished products, wholesalers can earn over $1,000 per kilogram.

The human rights violations described here represent only a fraction of the broader social and individual costs embedded in the extraction of critical minerals for solar and wind technologies. These harms are largely invisible in mainstream economic analyses, which tend to focus narrowly on construction costs, carbon emissions, and electricity output while ignoring the suffering borne by marginalized communities in the Global South. When the loss of livelihoods caused by lithium mining is weighed alongside the irreversible depletion of fragile water systems, and when the lifelong health consequences faced by children exposed to toxic dust and denied education are taken into account, the economic calculus surrounding renewable energy shifts significantly. Children forced into dangerous labor perpetuate cycles of poverty that extend far beyond the mines themselves, while Indigenous communities stripped of land and water lose the foundations of their cultural and economic survival. Accounting for these realities reveals that the transition to solar and wind energy, as currently structured, externalizes its most devastating costs onto those least responsible for climate change. Without meaningful supply-chain transparency, stronger labor protections, and enforceable ethical sourcing standards, the promise of “clean” energy remains compromised by the hidden human suffering that makes it possible.

In the next post I will discuss possible solutions to human rights violations in mining for critical minerals.