The Danger of Hope Alone: Why Waiting Out Climate Change Is a Risk We Can’t Afford

Part 2: The Cost of Inaction

In Part 1, we explored how passive hope—simply waiting and wishing for things to get better—can be a dangerous illusion in the face of climate change. Now, in Part 2, we examine the mounting costs of inaction.

Since the dawn of industrialization, Earth’s temperatures have steadily risen. Scientists have understood the link between increased carbon dioxide (CO₂) levels and rising global temperatures since at least the 1950s. Since the 1980s, this warming has accelerated significantly—doubling in pace between 2010 and 2020.

Experts warn that global temperatures must not exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. Yet we are already at approximately 1.2°C—and the consequences are unfolding before our eyes: more frequent and intense tropical storms, so-called “once-in-a-century” floods, prolonged droughts, rampant wildfires, extreme heatwaves, and repeated severe winter storms. These are no longer anomalies; they are the norm.

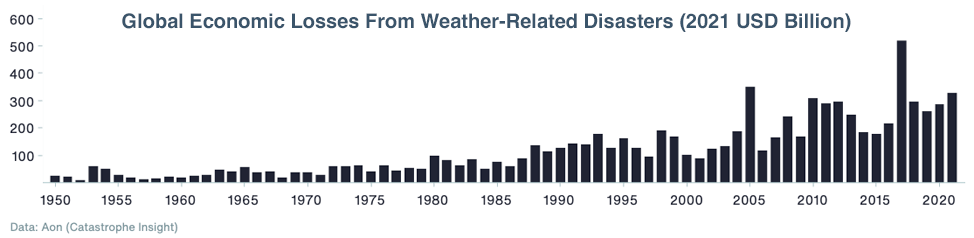

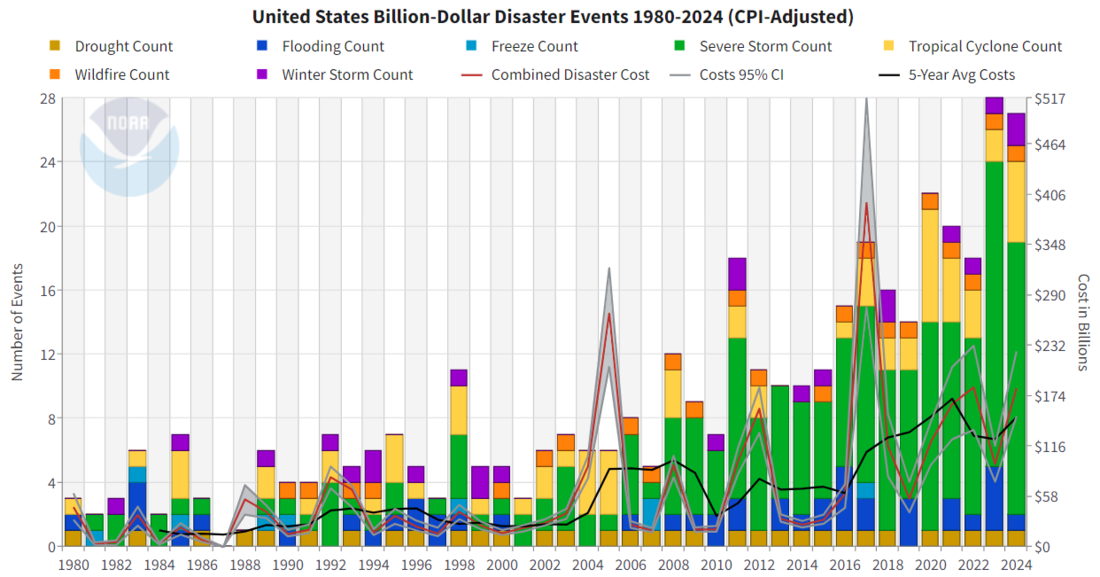

The toll—both human and economic—is staggering. Globally, between 1993 and 2022, more than 9,400 extreme weather events claimed nearly 800,000 lives and caused over $4 trillion in damages. In the United States since 1980, the U.S. has experienced 403 so called billion-dollar climate disasters. These events have resulted in nearly 17,000 death and caused close to $3 trillion in damages. Adjusted for inflation, the per capita cost of billion-dollar weather disasters in the U.S. has surged from $175 in 1980 to $1,573 in 2024. The financial and the human toll of these events are sure to increase due to the increase in frequency of such events. While the annual average is 9.0 events, in the last five years (2020-2024), the average has been 23 events.

Rising global temperatures are also pushing Earth closer to several critical tipping points—thresholds that, once crossed, could trigger irreversible changes, even if emissions are drastically cut.

One such tipping point is the thawing of permafrost, which is releasing methane that has been trapped underground for thousands of years. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, with heat-trapping power many times greater than CO₂. Another danger lies in the melting of polar and Greenland ice sheets. This process will dramatically alter Earth’s climate systems in several ways: With less reflective ice cover, more of the Sun’s heat is absorbed by land and sea, further accelerating warming.

The influx of freshwater into oceans could disrupt major currents like the Gulf Stream, destabilizing global weather patterns. Sea levels will rise significantly—measured in feet, not inches—threatening coastal regions and major global cities such as New York and Cairo. Tropical rainforests are also under threat.

The Amazon, for instance, holds around 200 billion metric tons of carbon—roughly one-quarter of all carbon stored on land. Shifting rain patterns and longer dry seasons, driven by climate change, could transform the Amazon from a vital carbon sink into a major source of emissions. Meanwhile, widespread deforestation—especially in tropical regions—reduces the Earth's natural ability to absorb greenhouse gases. In the short term, this means an increasing amount of carbon will remain in the atmosphere, accelerating climate change even further.

In Part 3, we’ll explore the promise—and limitations—of relying on future innovations to fix the mess we’re still making.