Microplastics

The Invisible Ingredient on Our Plates

In 2022, global plastic production exceeded 400 million metric tons—more than the total weight of all humans combined. As these plastic products age or undergo regular use, they gradually break down and release microplastics—tiny particles no larger than five millimeters or about 0.2 inches. Each year, an estimated 10 to 40 million metric tons of these particles are released into the environment.

Microplastics have now been detected in nearly every corner of the planet—from ocean floors to mountain peaks, in Arctic ice, rainwater, soil, lakes, and in rivers. Microplastics have been found in a wide variety of species, including zooplankton, fish, shellfish, birds, and even large marine mammals and humans. They are also present in tap water, bottled water, and even sea salt.

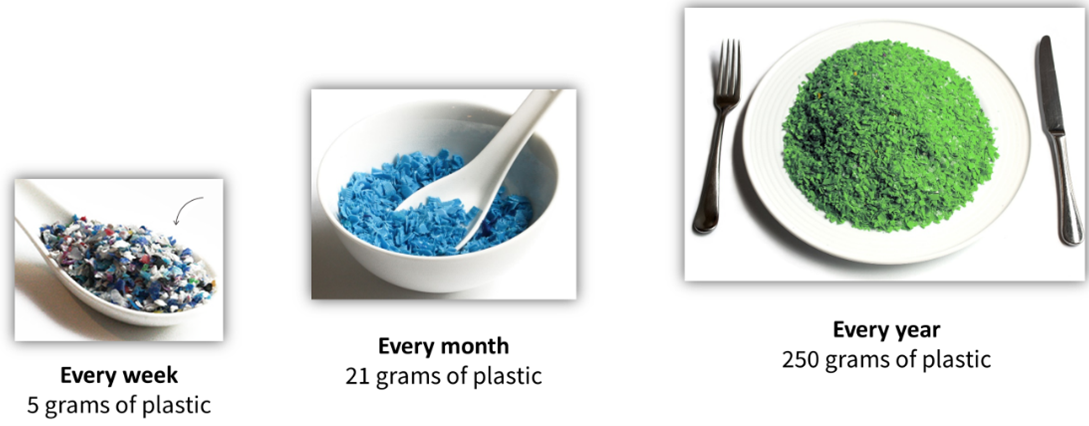

Humans are primarily exposed to microplastics through the food they consume, the water they drink, and the air they breathe. Once inside the body, these particles can accumulate over time, potentially affecting vital systems such as the gut, brain, heart, metabolism, and even individual cells.

Kitchen tools are an important source of microplastic in food. Plastic cutting boards can shed tiny fragments when used, which can then end up in food we eat. Blenders and grinders, especially when used on hard ingredients, can generate thousands or even millions of particles during normal operation. As plastic items age, they become increasingly fragile and more likely to break apart. Nonstick cookware coated with materials like Teflon or PTFE also poses a risk; once scratched or worn, these surfaces can release large quantities of microplastics during cooking.

Containers and utensils made from plastic are another source of contamination, particularly when exposed to heat. Heating food in plastic containers or using them with hot liquids can cause them to degrade and shed particles. Even cold temperatures can make some plastics brittle, increasing the chance of fragmentation. Disposable food packaging, such as takeout containers, is also known to release microplastics directly into meals.

Cleaning practices contribute to the problem as well. Sponges made from synthetic materials can release hundreds of microplastic particles in under a minute, even without soap or water. Over time, a single sponge can release tens of thousands of particles, particularly from the rougher side. Dishwashers, which contain plastic components, also wear down and shed particles into wastewater. In addition, some dishwashing detergents contain microplastics themselves. Kitchen sink sealants made from silicone have also been found to release microplastic particles through everyday wear and tear.

The use of disposable cooking aids adds even more microplastics to the mix. Nylon cooking bags, commonly used for roasting, can release trillions of particles during regular use. Nonwoven pouches used for cooking or steeping herbal mixtures have also been shown to shed substantial amounts of microplastics in a short amount of time. Plastic cling film, particularly when heated, may leach both chemical residues and microscopic plastic fragments into the food it touches.

Even the way food is cooked can influence the presence of microplastics. Cooking methods that involve lower temperatures and moisture, such as boiling or steaming, may reduce the amount of plastic that leaches into food. In contrast, dry, high-heat techniques like frying or roasting can increase both the number and size of microplastic particles.

Although it may be invisible, the kitchen is a significant and constant source of microplastic exposure. Fortunately, by making more conscious choices—such as selecting safer materials for cookware and utensils, avoiding heating food in plastic, and replacing worn or aging items—we can help protect our health and reduce the long-term environmental impact of plastic use.