Is the world at the start of a second “Scramble for Africa?”

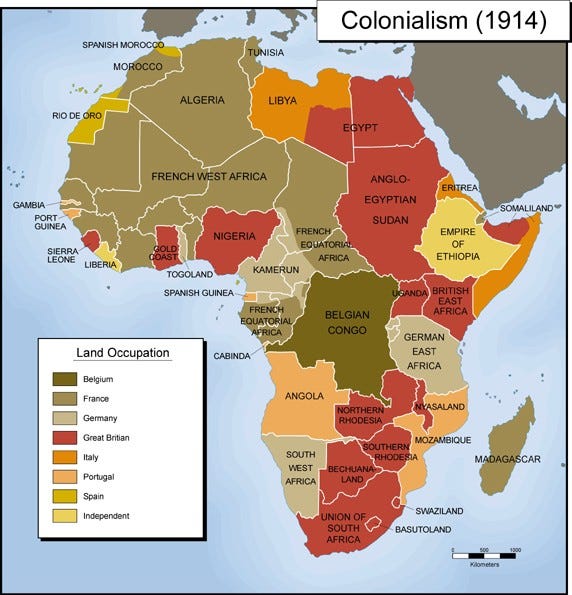

Between the 1880s and WWI European countries raced to occupy the African continent, seeking economic and strategic gains. The British control stretched from the southern tip of the continent to Egypt in the northeast.

France controlled most of the northwestern and some of the central parts of Africa. Germany had possessions in East Africa. Portugal laid claim to the southwestern corner of the continent. Italy took Libya from the Ottomans and King Leopold II of Belgium took personal ownership of Congo, an area the size of the United States east of the Mississippi River.

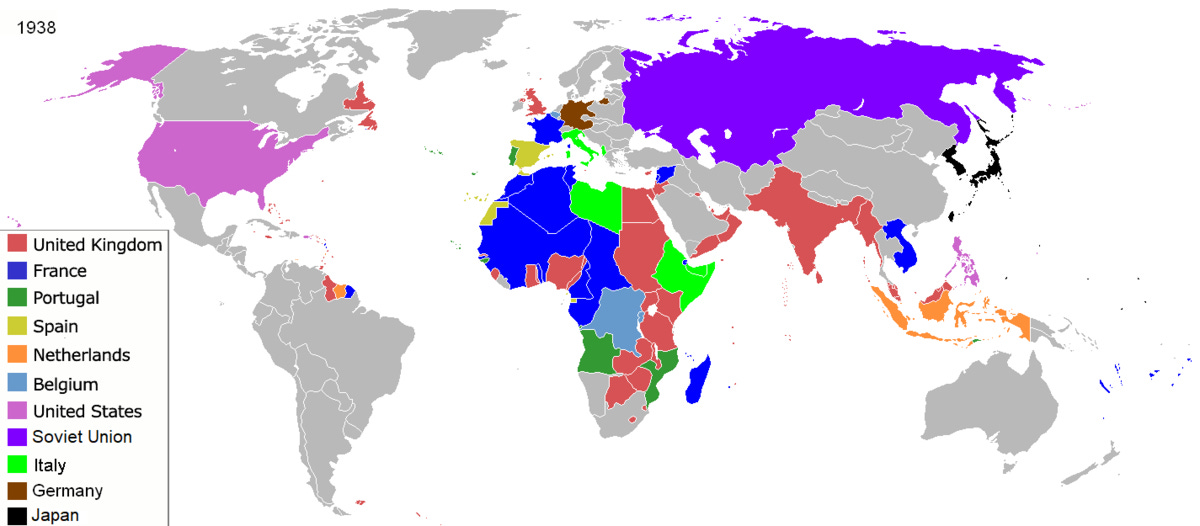

Similar patterns unfolded in other parts of the world. The USA occupied the Philippines and parts of the Caribbean while advancing its corporate investments in Central and South America. France and the Netherlands divided up Southeast Asia. Britain gained an oil concession in Iran and after the First World War, it took over modern-day Iraq with its vast oil reserves.

Gold, diamonds, cotton, rubber, coal, and oil powered the industrial economies of European powers. Cars and ships traveled on Middle East oil. Rubber was brought in from Congo, Amazon, and Vietnam. Electrical and motor industries used copper found in Chile, Peru, Zaire, and Zambia. An entirely new culture of mass consumption soon began to evolve. Britons drank tea imported from India and Ceylon. Americans and Germans imported coffee from South America. Chocolate was imported from West Africa and South America. Soap manufacturers look to vegetable oils from Africa. The colonies acted as markets for the manufactured goods that their natural resources had enabled their colonial masters to build.

The pattern of appropriation of cheap commodities and labor from poorer parts of the world by industrial countries continued apace following decolonization. From 1960 to 2018, the global North appropriated from the global South commodities worth $62 trillion or $152 trillion when accounting for lost growth. In fact, for the global North the gains are so large that, since 1990, they have outstripped the economic growth rate, suggesting that net growth in the global North depends on appropriation from the rest of the world (1).

Today the world is approaching another scramble for Africa as well as for other parts of the global South. The industrial nations of the global North along with China are seeking to secure access to minerals necessary for the development of renewable energy. Africa remains a particularly attractive prospect. It is home to a sizable share of critical minerals required for this massive undertaking. But critical minerals are also found in other parts of the world including in countries of the global South.

Once again, there is the old emphasis on low prices and the importance of uninterrupted supplies. Facing climate breakdown, a global problem that requires global solutions, however, the world must find answers to several important questions: Should the advanced countries and their corporations be allowed to access critical minerals at the cheapest possible prices? That would certainly allow people living in the global North and China to enjoy the fruits of clean energy at affordable prices. But what about the access to clean energy in the global South where most of the world’s population lives and their long-term sustainable developmental needs that require large annual investments? On one hand building clean energy infrastructure requires large amounts of minerals. On the other hand, building a sustainable energy system requires a global effort involving both the global North and the nations of the global South. How can we avoid climate breakdown if most of the world does not have the financial means to convert to clean energy? How can we persuade multinationals and their governments to support fair prices for minerals? How about consumers, let's say in North America, since fair mineral prices would mean higher prices for clean energy?

The solutions are only too obvious if difficult to implement. They require a fundamental change in power relations between the global South and the global North. Most importantly, poor nations must be allowed to develop their independent industrial capacity. To raise the investment needed, changes must be made in how the market-based world economic system is run by industrial states and their corporations. Poorer countries must be allowed to raise tariffs on imports and taxes on foreign corporations. An international framework is necessary to guarantee a minimum price for natural resources. American and European support for authoritarian regimes must be withdrawn to allow for the emergence of popular participation in economic decisions. These developments will result in the required democratization of the institutions of global economic governance, giving a real voice to the majority of the world’s people in how the IMF, the World Bank, and the WTO are used. It is only then that the world can have a realistic hope for successful development and to stop climate and environmental breakdowns facing the planet that everyone shares. Every one of these changes requires the global North and multinational corporations to share power.

History shows they will not do so voluntarily.

(1) Jason Hickel, et.al, Plunder in the Post-Colonial Era: Quantifying Drain from the Global South Through Unequal Exchange, 1960–2018, New Political Economy, March 2021.