How seriously should we take corporate sustainability claims?

Most corporations are publicly committed to what is loosely called “sustainability.” Source Half of the world’s largest companies are pledged to reach net zero at some point in the future. Source As the United Nations defines it, net zero refers to “cutting carbon emissions to a small amount of residual emissions that can be absorbed and durably stored by nature and other carbon dioxide removal measures, leaving zero in the atmosphere.” Source

The majority of the world’s largest companies are also publicly committed to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which aim to “address the global challenges we face, including those related to poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace, and justice.” Source

Investment in companies with high ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) ratings has been increasing rapidly in recent years Source and are expected to increase by 84% by 2026. Source ESG ratings provide investors with information on a corporation’s performance in these areas, making companies that do not harm the environment and are committed to social well-being more attractive to investors. These ratings also offer corporations third-party feedback on their sustainability policies.

With the corporate adoption of net zero targets, integration of SDGs in corporate planning, and investors' interest in ESGs ratings, corporations appear to be ready to play their role in creating a sustainable world. But are these corporate sustainability measures effective? And relatedly, do corporations take their sustainability commitments seriously?

Are corporate sustainability measures effective in safeguarding the environment?

It is difficult to determine the effectiveness of corporate sustainability measures in mitigating human-induced environmental changes. In their second warning to humanity in 2017, thousands of world’s scientists noted that “humanity has failed to make sufficient progress in … solving these foreseen environmental challenges (i.e., climate change, deforestation, freshwater depletion), and alarmingly, most of them are getting far worse.” Source In 2019, most of the same group of scientists called climate change an emergency, stating, “We declare clearly and unequivocally that planet Earth is facing a climate emergency. To secure a sustainable future, we must change how we live. [This] entails major transformations in the ways our global society functions and interacts with natural ecosystems.” Source

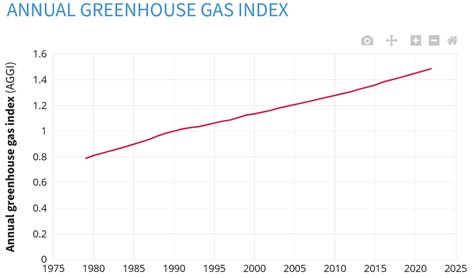

Since this declaration, greenhouse gas emissions have continued to rise. By the end of 2022, "the direct warming influence of human-produced greenhouse gases had risen 49 percent since 1990.” Source

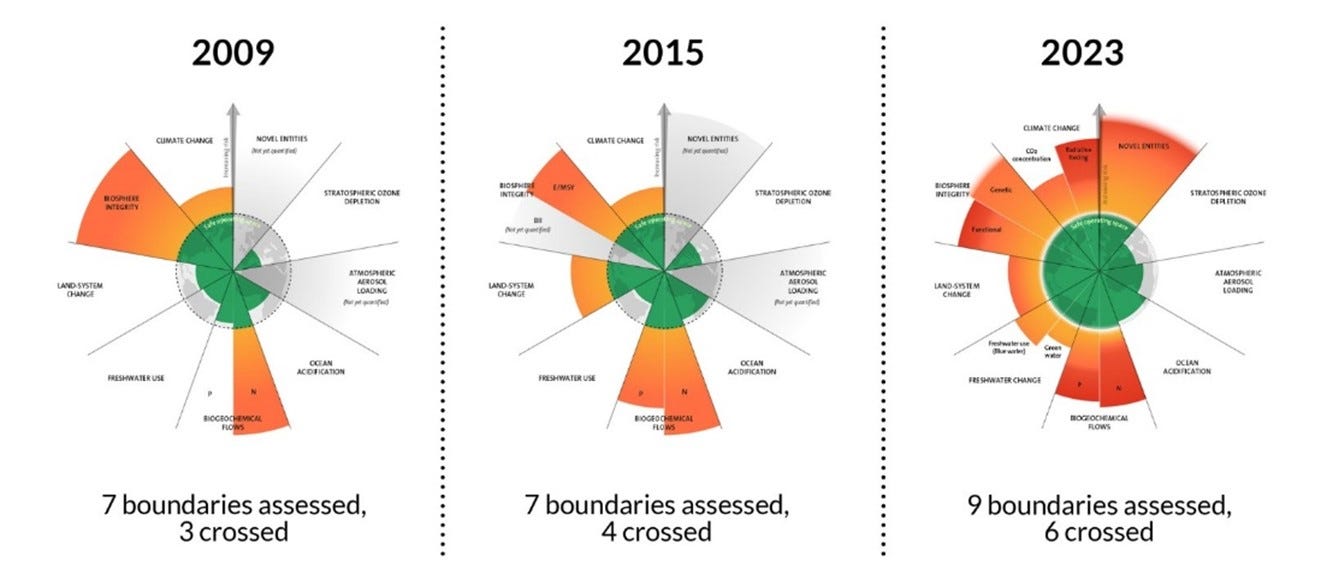

https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/planetary-boundaries.html

The United Nations estimates a further 9% increase in emissions by 2030, the year when the emissions should have been reduced by 45% to keep temperature increases at 1.5°C above preindustrial levels. Source

https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-annual-greenhouse-gas-index

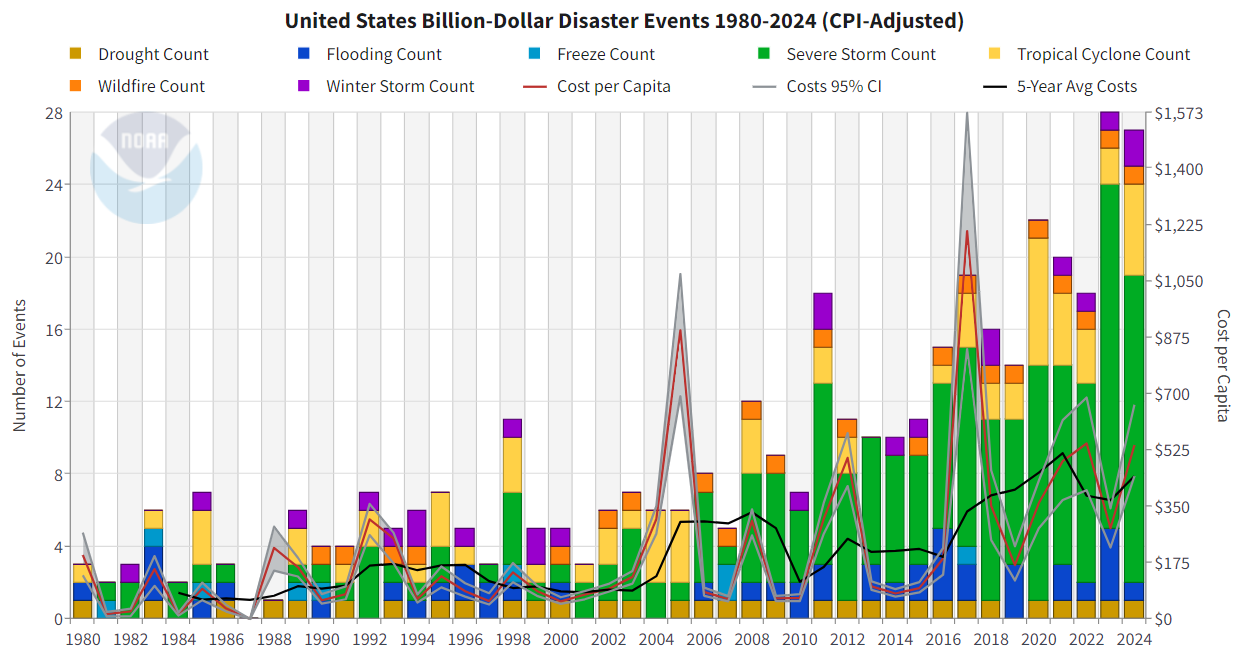

Indeed, the consequences of global warming have become increasingly clear to the public with frequent “historic” floods, heatwaves, wildfires, and droughts. By 2021, 67% of Americans could “perceive” a rise in extreme weather events. Source A study of 17 countries, including the United States, showed 60% of those sampled had experienced severe weather in 2022 and 2023. Source

https://www.climate.gov/media/16723

With accelerating rate of global warming, more people are expected to personally experience the consequences of severe weather events. Source

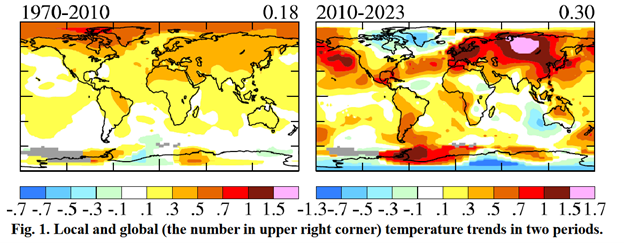

https://www.columbia.edu/~jeh1/mailings/2024/Hopium.MarchEmail.2024.03.29.pdf

Are corporations serious about “sustainability?”

Do companies take their own net zero pledges seriously? The 2024 Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor (CCRM) report, analyzing the climate strategies of 51 major global companies, found their net-zero targets ambiguous and lacking sufficient commitments to align with the 1.5°C target by 2030. The report states that companies' commitments would add up to only a 30% average emission reduction by 2030, falling short of the necessary average of 45% relative to 2019 emission levels set by the IPCC. The report warns that “[m]ost companies continue to present 2030 and net-zero targets that are either ambiguous or only commit to limited emission reductions. Often, targets cannot be taken at face value as companies leave out certain emission sources, use non-harmonized base years, do not report updated base year emissions, or do not provide contextualizing information to understand what the targets mean in absolute terms, among other issues.” Source (The better known Science Based Target Initiative paints a more positive picture of corporate commitments. However, it is important to keep in mind that SBTi is sponsored by large corporations such as Amazon and allows companies to use carbon credits and carpon offsets to meet their scope 3 emission targets.)

Similarly, Jack Arnold and Perrine Toledano’s study of 35 top-rated companies across seven sectors that are responsible for 64% of scope 1 emissions (GHG emissions released into the atmosphere due to the company’s operations) found most do not have short-term emission reduction targets and their medium- and long-term emission reduction targets do not align with their own science-based targets. Furthermore, 83% do not consider emission reduction as a factor guiding their future capital investment, two-thirds rely on carbon offsets to achieve their stated emission reduction pledges, and two-thirds do not have lobbying policies in support of the Paris agreement. Source

Do companies with a stated commitment to SDGs take those commitment seriously? Research by Amanda Williams, Patrick Haack, and Knut Haanaes found that most companies use SDG engagement for PR and reporting purposes. However, three companies were noted for their deep commitment to SDGs. These companies have clear yardsticks to measure SDG-related revenues, their corporate purpose is closely integrated with SDGs, and they innovate and partner for maximum SDG impact. Source

Are companies on the ESG portfolio do a better job of protecting the environment and addressing societal issues? Brian Tayan’s review of the literature shows that "ESG ratings have low associations with environmental and social outcomes." In fact, ESG-rated companies often have poorer compliance records with labor and environmental laws compared to non-ESG companies. Additionally, U.S. firms committed to incorporating ESG factors into their decision-making processes have poorer ESG ratings than those that do not make this commitment. Source

What explains this apparent lack of serious commitment to sustainability?

Surveys have shown that climate change and sustainability rank low on the list of important issues for global CEOs. According to PwC’s 2024 report, global CEOs see climate change near the bottom of the list of issues that can determine how they will do things differently in the next three years, far less important than geopolitical conflicts and inflation. The same survey showed climate change and related socio-economic inequality to be near the bottom of the threats CEOs feel their businesses are exposed to. Source The results were similar to PwC’s surveys taken between 2018 and 2022.

Similarly, Deloitte’s 2024 survey found that CEOs ranked environmental matters, including weather-related impact on their businesses, low among external threats to their business strategy. CEOs noted geopolitical instability as the most important threat, followed by regulations and inflation as most important threats. Source

This lack of concern aligns with the short-term profit motives of shareholders. The 2021 Deloitte survey of 2000 C-suite executives found that while many were personally concerned about climate change, they felt constrained by shareholders' short-term business concerns. Other obstacles cited included difficulty measuring environmental impact, a lack of sustainable inputs, cost, and the magnitude of the effort required. Source

Short-termism among investors is unsurprising given their wealth and resulting lifestyle. Between 2016 and 2021, about 85% of stocks in the United States were owned by the wealthiest 5%, with the richest 1% alone owning around 40% of stocks. The concentration of stock ownership has in fact been increasing steadily since 2011. By the end of 2023, nearly 50% of stocks were owned by the richest 1% in the U.S. Source Source

Oxfam’s "The Survival of the Richest" (2023) highlights the extreme concentration of wealth: the richest 1% have captured almost two-thirds of all new wealth since 2020, while inflation outpaces wages for over 1.7 billion workers. Food and energy companies have doubled their profits, paying out $257 billion to wealthy shareholders while over 800 million people go to bed hungry. Only 4 cents of every dollar of tax revenue comes from wealth taxes, and half the world's billionaires live in countries with no inheritance tax. Source

Oxfam's 2019 report noted that the richest 1% were responsible for 16% of global emissions, as much as the emissions of two-thirds of the world's population. The richest 10% accounted for 50% of emissions.

In the United States, the differences were more stark. The emissions of the top 1% were 25 times larger than those in the bottom 50%. These figures raise a fundamental question: Can we expect the top 1% to adopt an eco-friendly lifestyle in the face of a deteriorating environment? If history is a window to the future, the answer must be a resounding no. As Oxfam reported, “[w]hile people in the bottom 50% of income reduced their emissions by more than a fifth over the past 30 years, those in the top 1% have not reduced their average emissions at all. Source

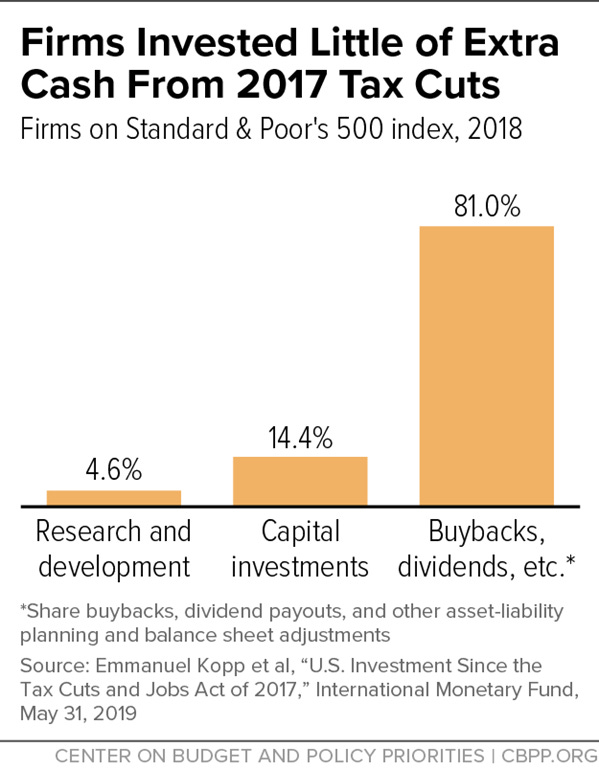

The stock buyback frenzy following the 2017 U.S. tax cuts further points to corporate short-termism. These buybacks favored ultra-wealthy shareholders by increasing stock value while limiting corporate investment in sustainable operations. Additionally, the tax cut denied the U.S. government $1.9 trillion in tax revenues over ten years, reducing the government’s ability to ensure sustainable development.

What is the most promising route to rapid change toward a sustainable future for all of humanity? I will try to answer this daunting question in my next blog.